Birsh (2018) defines phonemic awareness using The Partnership of Reading’s definition “as the ability to notice think about and work with the individual sounds in words (2003, p. 2). Phonemic awareness is an essential toward learning how to read as it helps children connect the spoken word to written language Birsh (2018). How does multisensory approaches facilitate phonemic awareness in children? Farrell & White (2018) suggest that “multisensory strategies guide students to in simultaneously linking input from eye, ear, voice, and hand to enhance learning during the carefully sequenced teaching of all systems of language” (p. 47). Phonological stimulation must begin as early as possible. Sensory stimulation through a multisensory approach of increased “auditory modeling and feedback, tactile stimulation of the articulators, visual feedback through clinician modeling, picture models of articulatory placement and the use of mirrors build cognitive connections to phonological awareness” Pierettie, Kaul, Zarchy, & O’Hanion (2015) Adoption of multisensory approaches assists teachers in facilitating multiple avenues toward improved cognition and fully involve students to an improved learning experience.

What does a multisensory approach to teach phonemic awareness look like in an early learning environment? Segmenting is a phonemic awareness task introduced later in the hierarchy of teaching phonemic awareness. Children learn segmenting of phonemes as they learn to identify and sort objects beginning with the same sound and later progress to focus on words with the same ending sound. An auditory task that teachers could incorporate besides saying a new vocabulary word through segmenting and blending might be to give directions using in a robot voice. Students could also make a bead slide, in which children use beads to move on a string to break the word into individual sounds as the teacher and children say the sound aloud. Teachers can use shoelaces and beads to complete this activity. This activity leverages both auditory and kinesthetic activities to assist with teaching segmentation. Games are a fun approach toward teaching the segmenting phonemic awareness task and can incorporate auditory, kinesthetic, and visual cues. For example, using “Elkonin boxes to tap a finger or place a chip in a designated box to match the number of syllables to a word” (Paulson, 2018). After a teacher models this activity, students can take turns saying and moving a chip or token. Over time the visual cue or box can eventually be eliminated from this activity.

Strengthening cognition through multisensory approaches during early literacy will promote successful decoding when reading, which will allow for additional time and energy to be focused on reading comprehension (Pierettie, Kaul, Zarchy, & O’Hanion, 2015). Understanding how to leverage multisensory approaches to strengthen phonological awareness in early childhood programs can lead to an improved early intervention program. An emphasis on multisensory approaches within new teacher training could assist in building a stronger phonemic awareness early literacy program.

Pieretti, R. A., Kaul, S. D., Zarchy, R. M., & O’Hanlon, L. M. (2015). Using a multimodal approach to facilitate articulation, phonemic awareness, and literacy in young children. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 36(3), 131-141.

Birsh, J. R. & Carreker, S. Multisensory teaching of basic language skills (4th Ed). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Farrell, M., White, N. C. (2018). Structured literacy instruction. In Birsh, J. R. & Carreker, S. Multisensory teaching of basic language skills (4th Ed). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Paulson, L. H. (2018). Teaching phonemic awareness. In Birsh, J. R. & Carreker, S. Multisensory teaching of basic language skills (4th Ed). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

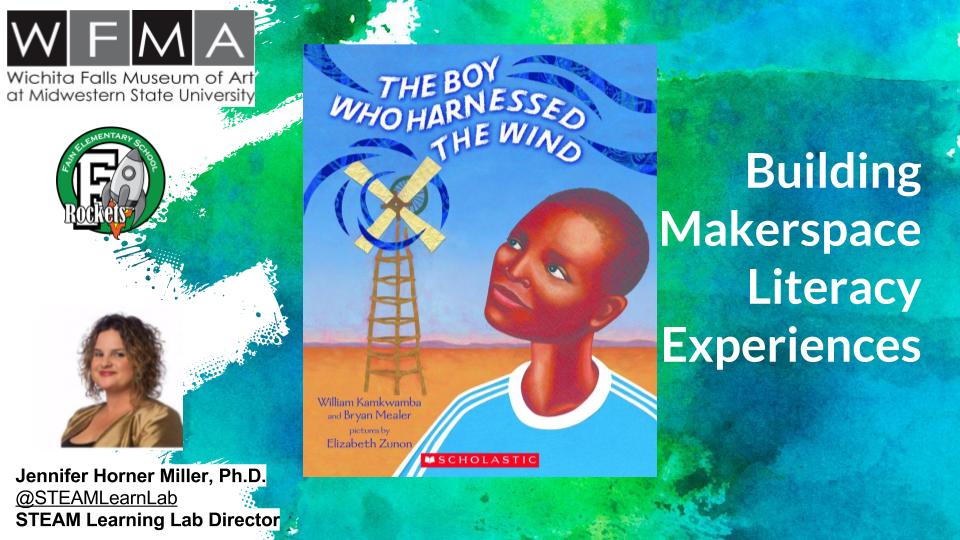

Social constructionism “relies on the centrality of language to mediate what people come to understand about their lived experiences” (Avermann, 2011, p. 205). Constructionist environments support “active learning” approaches in which learners are engaged in building their own public objects or artifacts. Active learning emphasizes cognitive processes occurring during the actual construction of the object. The public nature of the final object or artifact is also understood to be important (Beynon & Roe, 2004). The “maker movement emphasizes learning through direct experiences, hands-on projects, inventions, and is based on a constructionist learning theory even if members and advocates of the movement are unaware of the theory” (Stager, 2013). Papert (2000) advocates that Piaget’s belief of all learning takes place in discovery is accurate. However, Papert extends this idea to suggest that setting learners “to the task of re-empowering the ideas of being learned is also a step toward re-empowering the idea of learning by discovery” (p. 723). Papert (1999) underscores the importance of Piaget’s theory of constructivism and the nature of knowledge. Challengers of Piaget’s constructivism often refer to experiments demonstrating knowledge acquired by infants. However, Papert stresses “Piaget as a giant in the field of cognitive theory, the difference between what a baby brings and what the adult has is so immense that the new discoveries do not significantly reduce the gap but only increase the mystery” (Papert, 1999, p. 105). Papert’s Knowledge Machine” introduced the world to a new theory of learning, constructionism, which “synthesized revised insights into human development, systems theory (cybernetics) and how we think about learning (epistemology)” (Maser, 2013). Technology based modeling and methods of teaching with technologies deliver alternative methods to teaching, providing learners with choices that engage the learner in an improved learning experience (Burbaite, Stuikys, & Damasevicius, 2013). While at MIT, Papert developed Logo, designed to introduce children to programing and robotics as early as 4th grade. Children received instant feedback from a real and physical response to their creation using technology. Papert envisioned robotics as being extremely influential to children at a young age. Learners perform higher when engaged in an activity that is meaningful to them, and robotics along with programing languages encourages curiosity and experimentation beyond the actual syntax (Pierce, 2013). Papert led many research projects to study the effects of constructionist theories with at risk populations and in high-risk environments. These projects attempted to build an alternative approach to the learning environment. Despite obstacles, students proved to be successful. Experiences from Papert’s work towards building a community of learning centered on constructionism continues to guide the future design of learning environments (Stager, 2013).

Social constructionism “relies on the centrality of language to mediate what people come to understand about their lived experiences” (Avermann, 2011, p. 205). Constructionist environments support “active learning” approaches in which learners are engaged in building their own public objects or artifacts. Active learning emphasizes cognitive processes occurring during the actual construction of the object. The public nature of the final object or artifact is also understood to be important (Beynon & Roe, 2004). The “maker movement emphasizes learning through direct experiences, hands-on projects, inventions, and is based on a constructionist learning theory even if members and advocates of the movement are unaware of the theory” (Stager, 2013). Papert (2000) advocates that Piaget’s belief of all learning takes place in discovery is accurate. However, Papert extends this idea to suggest that setting learners “to the task of re-empowering the ideas of being learned is also a step toward re-empowering the idea of learning by discovery” (p. 723). Papert (1999) underscores the importance of Piaget’s theory of constructivism and the nature of knowledge. Challengers of Piaget’s constructivism often refer to experiments demonstrating knowledge acquired by infants. However, Papert stresses “Piaget as a giant in the field of cognitive theory, the difference between what a baby brings and what the adult has is so immense that the new discoveries do not significantly reduce the gap but only increase the mystery” (Papert, 1999, p. 105). Papert’s Knowledge Machine” introduced the world to a new theory of learning, constructionism, which “synthesized revised insights into human development, systems theory (cybernetics) and how we think about learning (epistemology)” (Maser, 2013). Technology based modeling and methods of teaching with technologies deliver alternative methods to teaching, providing learners with choices that engage the learner in an improved learning experience (Burbaite, Stuikys, & Damasevicius, 2013). While at MIT, Papert developed Logo, designed to introduce children to programing and robotics as early as 4th grade. Children received instant feedback from a real and physical response to their creation using technology. Papert envisioned robotics as being extremely influential to children at a young age. Learners perform higher when engaged in an activity that is meaningful to them, and robotics along with programing languages encourages curiosity and experimentation beyond the actual syntax (Pierce, 2013). Papert led many research projects to study the effects of constructionist theories with at risk populations and in high-risk environments. These projects attempted to build an alternative approach to the learning environment. Despite obstacles, students proved to be successful. Experiences from Papert’s work towards building a community of learning centered on constructionism continues to guide the future design of learning environments (Stager, 2013).