Gunderson (2013) highlights how technologies can create new opportunities and improve ELL literacies as long as barriers are addressed to improve teachers’ self-efficacy with a focus on technology skills and confidence in professional development, funding to address equity issues, and curriculum in place to address “Digital Disconnect” in schools. Many opportunities exist to improve L2 academic performance. Park & Warschuer (2016) provide compelling evidence to suggest that activating background knowledge through integration of technology using hyperlinked media can begin to address gaps and provide valuable resources. The Multiliteracy Project is one project that caught my attention as students are able to contribute to a meaningful project in their first language and utilizes many diverse literacies that connect to my research interest. The Multiliteracy Project website, http://multiliteracies.ca/index.php/stat/register, connects students to projects around the world using many forms of literacies that promote social responsibility. Gunderson (2013) shares how hyperlinks in one project. Students produce Blue Sea Creatures hyperlinks. This could be of interest to ELL students, as they are curating content and researching to locate valid information and media, to share with others. We are working on Texas land forms and I could see how ELL learners could use this idea using hyperlinks to create their own website. We could utilize both Spanish and English in hyperlinks to provide additional information to users in Google Sites.

Park & Warschaurer (2016) provide strong evidence as to how multi-modal vocabulary support can assist ELL learners. Encouraging ELL learners to “express themselves in multiple ways” can provide significant gains in academic vocabulary acquisition (Park & Warschurer, 2016, p. 288). Gunderson (2013) provides many resources and ideas on how to leverage visual imagery to improve comprehensible input. Diccts.info, https://www.dicts.info/, offers users easy search features and includes a universal dictionary, basic vocabulary, picture dictionary, English dictionary, Phrases, Bilingual dictionaries, Flashcards, Vocabulary trainer, English thesaurus, and Examples of use feature. I began searching the words that are using and found that the picture dictionary is limited. For instance, the word mountain and range are both not included in search results. Range is listed in results but does not populate a search result when selected. While this does serve as a good beginning resource, it highlights the issues facing teachers. I reviewed the PDictionary, http://pdictionary.com, and had a similar experience. I did locate cactus, which is a vocabulary word in this resource. These resources could be useful in teaching ELL students how to look up information, which Gunderson (2013) strongly encourages as a component of information literacy.

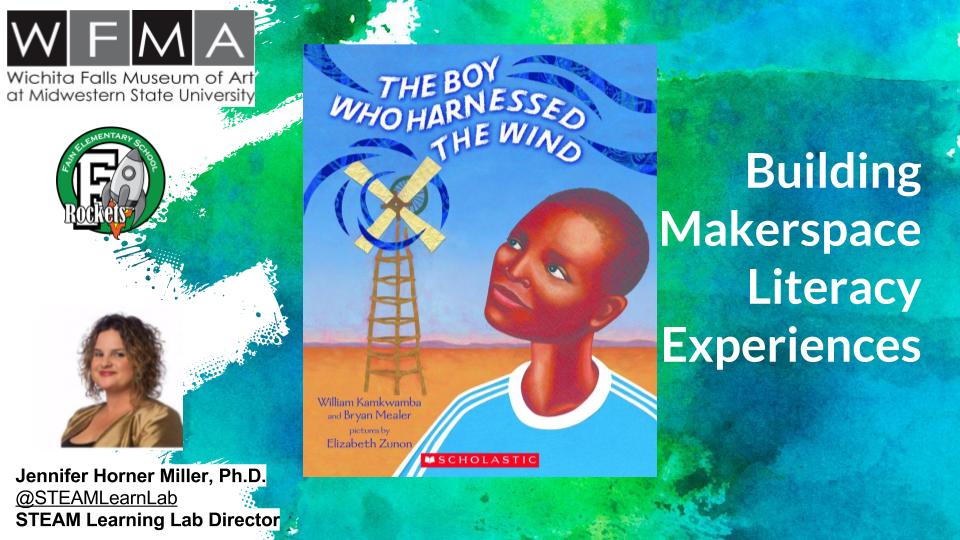

As a strong advocate of information literacy, I appreciate Gunderson’s (2013) approach toward teaching critical literacy online. To me this is the largest issue and serves to begin to finally address the Digital Disconnect Gunderson (2013) discusses. So many classrooms and curriculum teach technology as a skill set but this approach sometimes misses the mark. Digital literacy is more than a skill set, it is a critical thinking approach to validating information prior to possibility creating meaning and products. Therefore, I agree that we must teach online critical literacy skills in all courses and begin to address how to search information, how to evaluate media, and how to read online. I really Gunderson’s (2011) practices of “teaching reading online to identify important questions, to locate information, to critically evaluate information, to synthesize information, and to communicate information” (p. 247). In essence, all teachers should be required to address how to accomplish reading online through these five actions. I can suggest that we begin to do this for makerspace projects. One part of the makerspace process is research and through the making of the product, he will be creating and communicating his process online. So, I have decided to add a digital layer on the process. This will strengthen is use of vocabulary as ELL learners will select how the student communicates to share final productions online.

Gunderson, L., D’Silva, R., & Odo, D. M. (2013). ESL (ELL) literacy instruction: A guidebook to theory and practice. Routledge.

Park, Y. and Warschauer M. (2016) Reading instruction in a technological age. In X. Chen, V. Dronjic, & R. Helms-Park, Reading in a second language: Cognitive and psycholinguistic issues (pp. 282-302). New York: Routledge.

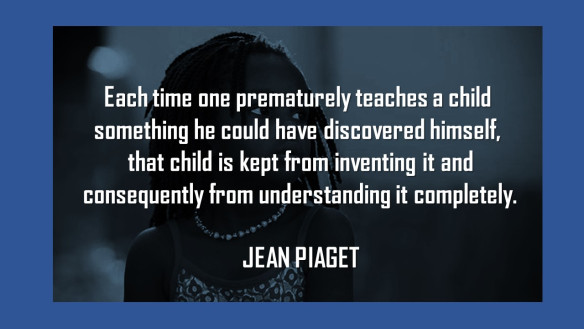

Social constructionism “relies on the centrality of language to mediate what people come to understand about their lived experiences” (Avermann, 2011, p. 205). Constructionist environments support “active learning” approaches in which learners are engaged in building their own public objects or artifacts. Active learning emphasizes cognitive processes occurring during the actual construction of the object. The public nature of the final object or artifact is also understood to be important (Beynon & Roe, 2004). The “maker movement emphasizes learning through direct experiences, hands-on projects, inventions, and is based on a constructionist learning theory even if members and advocates of the movement are unaware of the theory” (Stager, 2013). Papert (2000) advocates that Piaget’s belief of all learning takes place in discovery is accurate. However, Papert extends this idea to suggest that setting learners “to the task of re-empowering the ideas of being learned is also a step toward re-empowering the idea of learning by discovery” (p. 723). Papert (1999) underscores the importance of Piaget’s theory of constructivism and the nature of knowledge. Challengers of Piaget’s constructivism often refer to experiments demonstrating knowledge acquired by infants. However, Papert stresses “Piaget as a giant in the field of cognitive theory, the difference between what a baby brings and what the adult has is so immense that the new discoveries do not significantly reduce the gap but only increase the mystery” (Papert, 1999, p. 105). Papert’s Knowledge Machine” introduced the world to a new theory of learning, constructionism, which “synthesized revised insights into human development, systems theory (cybernetics) and how we think about learning (epistemology)” (Maser, 2013). Technology based modeling and methods of teaching with technologies deliver alternative methods to teaching, providing learners with choices that engage the learner in an improved learning experience (Burbaite, Stuikys, & Damasevicius, 2013). While at MIT, Papert developed Logo, designed to introduce children to programing and robotics as early as 4th grade. Children received instant feedback from a real and physical response to their creation using technology. Papert envisioned robotics as being extremely influential to children at a young age. Learners perform higher when engaged in an activity that is meaningful to them, and robotics along with programing languages encourages curiosity and experimentation beyond the actual syntax (Pierce, 2013). Papert led many research projects to study the effects of constructionist theories with at risk populations and in high-risk environments. These projects attempted to build an alternative approach to the learning environment. Despite obstacles, students proved to be successful. Experiences from Papert’s work towards building a community of learning centered on constructionism continues to guide the future design of learning environments (Stager, 2013).

Social constructionism “relies on the centrality of language to mediate what people come to understand about their lived experiences” (Avermann, 2011, p. 205). Constructionist environments support “active learning” approaches in which learners are engaged in building their own public objects or artifacts. Active learning emphasizes cognitive processes occurring during the actual construction of the object. The public nature of the final object or artifact is also understood to be important (Beynon & Roe, 2004). The “maker movement emphasizes learning through direct experiences, hands-on projects, inventions, and is based on a constructionist learning theory even if members and advocates of the movement are unaware of the theory” (Stager, 2013). Papert (2000) advocates that Piaget’s belief of all learning takes place in discovery is accurate. However, Papert extends this idea to suggest that setting learners “to the task of re-empowering the ideas of being learned is also a step toward re-empowering the idea of learning by discovery” (p. 723). Papert (1999) underscores the importance of Piaget’s theory of constructivism and the nature of knowledge. Challengers of Piaget’s constructivism often refer to experiments demonstrating knowledge acquired by infants. However, Papert stresses “Piaget as a giant in the field of cognitive theory, the difference between what a baby brings and what the adult has is so immense that the new discoveries do not significantly reduce the gap but only increase the mystery” (Papert, 1999, p. 105). Papert’s Knowledge Machine” introduced the world to a new theory of learning, constructionism, which “synthesized revised insights into human development, systems theory (cybernetics) and how we think about learning (epistemology)” (Maser, 2013). Technology based modeling and methods of teaching with technologies deliver alternative methods to teaching, providing learners with choices that engage the learner in an improved learning experience (Burbaite, Stuikys, & Damasevicius, 2013). While at MIT, Papert developed Logo, designed to introduce children to programing and robotics as early as 4th grade. Children received instant feedback from a real and physical response to their creation using technology. Papert envisioned robotics as being extremely influential to children at a young age. Learners perform higher when engaged in an activity that is meaningful to them, and robotics along with programing languages encourages curiosity and experimentation beyond the actual syntax (Pierce, 2013). Papert led many research projects to study the effects of constructionist theories with at risk populations and in high-risk environments. These projects attempted to build an alternative approach to the learning environment. Despite obstacles, students proved to be successful. Experiences from Papert’s work towards building a community of learning centered on constructionism continues to guide the future design of learning environments (Stager, 2013).