Currently, I teach six graduate education courses at Sul Ross State University, which is a small rural university serving 898 graduate students and a little over 2,000 undergraduate students. The institution is a Hispanic serving institution, serving low income students (Jenkins, et al., 2017). I am working with many rural schools in the Big Bend area to include Presidio ISD. Presidio ISD is a STEM school, and serves a population of 1,350 students to include demographics of 96.6 % Hispanic students and 93.4% economically disadvantaged students (2015). Presdio ISD is located on the Rio Grande river, located on the Texas-Mexican border. In addition, I am working with Maathon ISD, which is a rural district serving over 70 students to include a demographic population of 67 % Hispanics and 87 % economically disadvantaged students (2015). I am also working with several districts in the Trans-Pecos area.

My learning goals this academic year is to grow as an educator and continue improving my Ph.D. research initiatives at the University of North Texas investigating makerspace literacy environments that centers around a project-based learning 4 career STEAM model targeting elementary and middle school programs. My knowledge regarding the reading process has definitely changed and improved this semester. Perhaps the most significant change includes reevaluating my approach to really center on balanced literacy approaches that really think about transactional theory in action during professional development and instructional design approaches. Transactional theory centers on “how readers respond to the books that engage them and how these experiences can be enacted in classrooms” (Galda, 2013, p. 6). Transactional theory is rooted in Vygotsky’s social constructivism and principles of language and cognition, “which centers of teaching reading and writing highlighting creation of environments and activities in which students are motivated and encouraged to draw on their own resources to make live meanings” (Rosenblatt, 2013, p. 148).

What will I eliminate in the future? I will eliminate some of the STEM quantitative measures I have used in the past. These instruments were only used to show interest and attitude toward STEM and never measured the impact on the overall impact of literacy. Previously, I would give this instrument before and after a STEM makerspace camp or at the beginning of a semester and at the end of a semester to gauge interest. I utilized the makerspace project-based learning model and only measured the impact of interest. The model did incorporate reading prior to the makerspace PBL and a written reflection after the experience. The pre and posttest utilized in two published studies found statistically significant findings but failed to measure the impact on reading and literacy. The learner would take the STEM Semantic pre-test, read text from their content area, participate in a KWLH 21st century learning activity, participate in a makerspace project-based learning activity using challenge cards mapped to curriculum, and reflect via writing about the experience. At the end, learners would take another post-test, the STEM Semantic survey. I have not really considered the empirical design approaches to include journaling during the entire makerspace process and/or video recordings to include in portfolios in research approaches. In the past, I have used only quantitative measures to gauge student or teacher interest and confidence levels pre and post over a period of time. While the instruments we used at the University of North Texas are widely accepted as strong and valid instruments, I now realize that a mixed method approach to include journaling throughout the experience and video interviews and reflections would add further depth to capture the impact of the STEAM makerspace challenge cards before and after literacy events. In addition, I feel this would really add to the field of sociolinguistic issues discussed this semester. I now have a stronger understanding on how to leverage native language and family cultural heritages in the makerspace model to not only improve literacy in English Language Learners but also to value the funds of knowledge to this process.

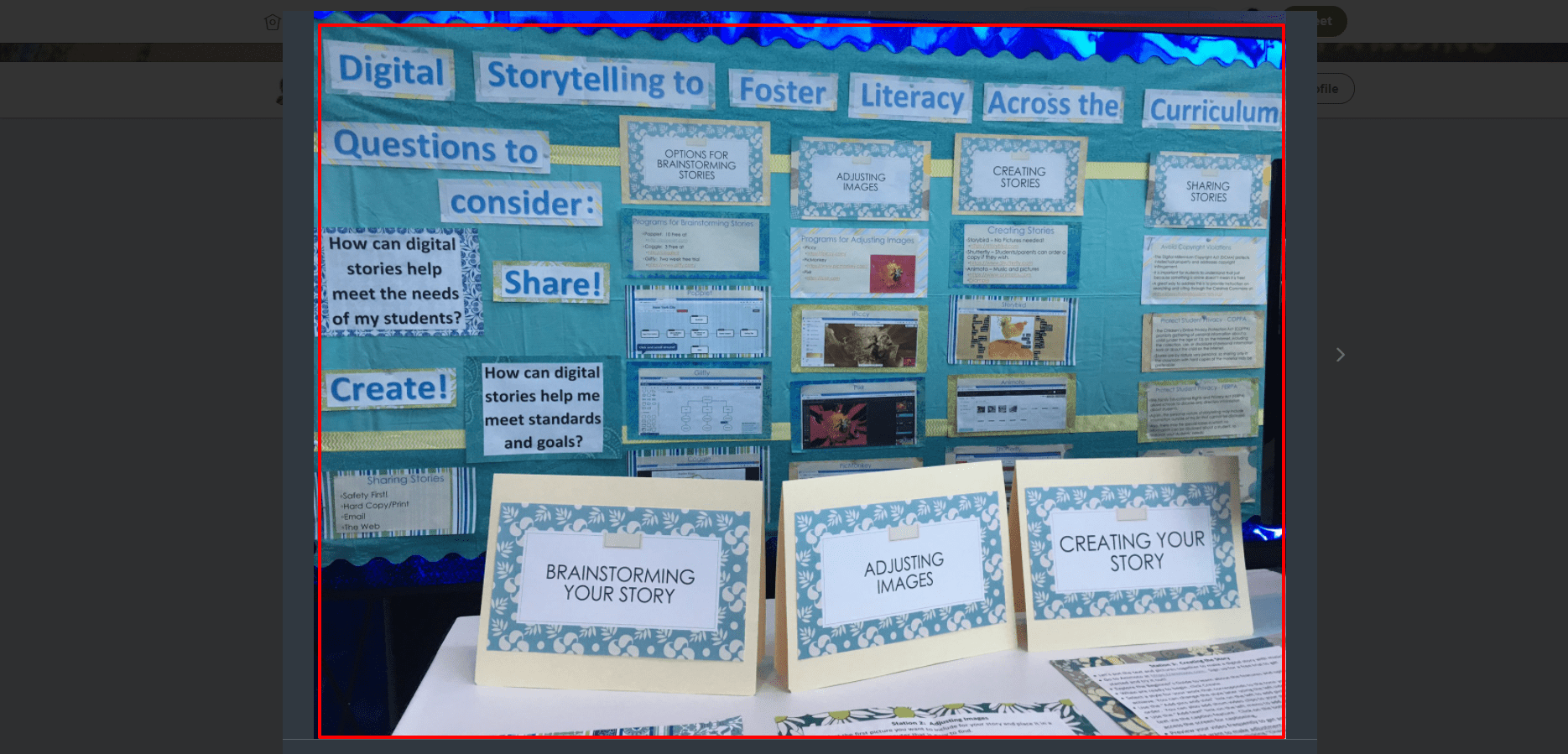

How can this approach help increase literacy opportunities for English Language Learners? First, I need to strengthen the collaborative dialogue, which I feel is strong in the KWLH activity. However, I can improve the scaffolding of my model to include previewing a picture book, vocabulary discussion, incorporating a story map, repeat reading of the story, compete the KWHL activity, and then encourage discourse after the makerspace activity. In addition, I can encourage video procedures and or reflections throughout the makerspace process. This will provide a visualization component that others may find beneficial and highlight the impact of the activity. Repeating readings can be used to measure fluency. The makerspace PBL activity using the challenge card concept could also include visualization to incorporate sociolinguistics highlighted in this course.

Tan, Barton, & Schenkel (2018) describe the impact of “meaningful and prolonged engagement toward focused complex projects through making experiences and found that children’s rich funds of knowledge anchored in children’s existing social networks provide community enthnography as a pedagogical approach (p. 77). Bringing in the “community wisdom” through makerspace activities brought about rich conversations that can really leverage experiences connected to curriculum in their own community (Tan, Barton, & Schenkel, 2018, p. 81). Range & Schmidt (2014) highlight the importance of schools and community organizations to tap into prior knowledge in makerspace activities and suggest that “students drive the process of designing projects and soliciting makerspace community for help” (p. 8). While I agree this is true, I still think many students need facilitation of such projects through a focus that may connect to core curriculum content, showing that topics can be extended to real world scenarios relevant to their community.

In conclusion, this course has helped me to really improve my understanding on how to better design literacy instructional design approaches to incorporate a large focus that centers on the transactions of the reader, text, language, culture, authentic making design process, writing, and reflection. I hope to revamp my approaches to really center on how such creative processes might not only engage interest in STEM but also build to improve cognition approaches toward multiple literacies in a mobile makerspace research environment that investigates reader response theory, or transactional theory

Galda, L. g. (2013). Learning From Children Reading Books: Transactional Theory and the Teaching of Literature. Journal Of Children’s Literature, 39(2), 5-13.

Jenkins, R. W., Stedman, S. W., Teusher, D. D., DeLaGarza, H. R., Acosta, A., Anwar, S. J., Paredes, R. A. (2017). Texas Public Higher Education Almanac.

Marathon ISD, (2015) Retrieved April 13, 2018 from https://schools.texastribune.org/districts/marathon-isd/marathon-isd/.

Presidio ISD. (2015). Retrieved April 13, 2018, from https://schools.texastribune.org/districts/presidio-isd/.

Range, E., & Schmidt, J. (2014). Explore, plan, create: Developing a makerspace for your school community. School Library Monthly, 30(7), 8-10.

Rosenblatt, L. Transactional theory of reading and writing. In J.B. Cobb, & M. K. Kallus (Eds.), Historical, Theoretical, and Sociological Foundations of Reading in the United States (pp. 13-66). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Tan, E., Barton, A. C., & Schenkel, K. (2018). Equity and the Maker Movement. Science and Children, 55(7), 76-81.

Social constructionism “relies on the centrality of language to mediate what people come to understand about their lived experiences” (Avermann, 2011, p. 205). Constructionist environments support “active learning” approaches in which learners are engaged in building their own public objects or artifacts. Active learning emphasizes cognitive processes occurring during the actual construction of the object. The public nature of the final object or artifact is also understood to be important (Beynon & Roe, 2004). The “maker movement emphasizes learning through direct experiences, hands-on projects, inventions, and is based on a constructionist learning theory even if members and advocates of the movement are unaware of the theory” (Stager, 2013). Papert (2000) advocates that Piaget’s belief of all learning takes place in discovery is accurate. However, Papert extends this idea to suggest that setting learners “to the task of re-empowering the ideas of being learned is also a step toward re-empowering the idea of learning by discovery” (p. 723). Papert (1999) underscores the importance of Piaget’s theory of constructivism and the nature of knowledge. Challengers of Piaget’s constructivism often refer to experiments demonstrating knowledge acquired by infants. However, Papert stresses “Piaget as a giant in the field of cognitive theory, the difference between what a baby brings and what the adult has is so immense that the new discoveries do not significantly reduce the gap but only increase the mystery” (Papert, 1999, p. 105). Papert’s Knowledge Machine” introduced the world to a new theory of learning, constructionism, which “synthesized revised insights into human development, systems theory (cybernetics) and how we think about learning (epistemology)” (Maser, 2013). Technology based modeling and methods of teaching with technologies deliver alternative methods to teaching, providing learners with choices that engage the learner in an improved learning experience (Burbaite, Stuikys, & Damasevicius, 2013). While at MIT, Papert developed Logo, designed to introduce children to programing and robotics as early as 4th grade. Children received instant feedback from a real and physical response to their creation using technology. Papert envisioned robotics as being extremely influential to children at a young age. Learners perform higher when engaged in an activity that is meaningful to them, and robotics along with programing languages encourages curiosity and experimentation beyond the actual syntax (Pierce, 2013). Papert led many research projects to study the effects of constructionist theories with at risk populations and in high-risk environments. These projects attempted to build an alternative approach to the learning environment. Despite obstacles, students proved to be successful. Experiences from Papert’s work towards building a community of learning centered on constructionism continues to guide the future design of learning environments (Stager, 2013).

Social constructionism “relies on the centrality of language to mediate what people come to understand about their lived experiences” (Avermann, 2011, p. 205). Constructionist environments support “active learning” approaches in which learners are engaged in building their own public objects or artifacts. Active learning emphasizes cognitive processes occurring during the actual construction of the object. The public nature of the final object or artifact is also understood to be important (Beynon & Roe, 2004). The “maker movement emphasizes learning through direct experiences, hands-on projects, inventions, and is based on a constructionist learning theory even if members and advocates of the movement are unaware of the theory” (Stager, 2013). Papert (2000) advocates that Piaget’s belief of all learning takes place in discovery is accurate. However, Papert extends this idea to suggest that setting learners “to the task of re-empowering the ideas of being learned is also a step toward re-empowering the idea of learning by discovery” (p. 723). Papert (1999) underscores the importance of Piaget’s theory of constructivism and the nature of knowledge. Challengers of Piaget’s constructivism often refer to experiments demonstrating knowledge acquired by infants. However, Papert stresses “Piaget as a giant in the field of cognitive theory, the difference between what a baby brings and what the adult has is so immense that the new discoveries do not significantly reduce the gap but only increase the mystery” (Papert, 1999, p. 105). Papert’s Knowledge Machine” introduced the world to a new theory of learning, constructionism, which “synthesized revised insights into human development, systems theory (cybernetics) and how we think about learning (epistemology)” (Maser, 2013). Technology based modeling and methods of teaching with technologies deliver alternative methods to teaching, providing learners with choices that engage the learner in an improved learning experience (Burbaite, Stuikys, & Damasevicius, 2013). While at MIT, Papert developed Logo, designed to introduce children to programing and robotics as early as 4th grade. Children received instant feedback from a real and physical response to their creation using technology. Papert envisioned robotics as being extremely influential to children at a young age. Learners perform higher when engaged in an activity that is meaningful to them, and robotics along with programing languages encourages curiosity and experimentation beyond the actual syntax (Pierce, 2013). Papert led many research projects to study the effects of constructionist theories with at risk populations and in high-risk environments. These projects attempted to build an alternative approach to the learning environment. Despite obstacles, students proved to be successful. Experiences from Papert’s work towards building a community of learning centered on constructionism continues to guide the future design of learning environments (Stager, 2013).