Over 50 million K-12 public school students learned remotely this past year, with 37% of students located in rural communities lacking broadband compared to 25% of suburban households and 21% of urban households lacking connectivity. Texas ranked highest in the nation, with 34% of students lacking broadband connection and 24% of students lacking access to a device (Chadra, Chang, Day, et. al, 2020). Post COVID-19 presents the immediate need to rethink digital leadership approaches to begin to address the digital divide presented by equity and accessibility issues. Research indicates English learners, students with disabilities, students experiencing homelessness, and students in foster care in middle and high school were all less likely than their peers to access district school platforms in the spring (O’Keefe & Repeka, 2020). Many schools in remote areas of far west and south Texas were fully remote in 2021. In fact, New Mexico schools were mandated to remote learning until late March 2021. What did we learn from this experience? How could leaders improve the strategic plan process to better address the needs of our students, specifically underrepresented populations, students with disabilities and remote schools serving at-risk populations?

Recognize and identify where the digital divide exists in your community.

Accessibility issues can no longer be defined in terms of physical access. The pandemic has shown that schools must approach the use of distance education and digital learning from an equity lens. Age does not define digital fluencies or abilities to apply digital skills to communicate effectively. The term ‘digital divide’ traditionally was used to describe inequities in access to devices and broadband, but this definition fails to capture gaps in educational experiences, curricula, and social, cultural, and economic realities of many (Gorski, 2005). This issue has long been debated in literature but school closures during the pandemic magnified preexisting socio-economic and education disparities on a massive scale, revealing large inequities in access to resources and learning quality (Vishkale, 2020). Schools must begin to truly identify gaps in accessibility to include physical access, technology mediums used, equity, resources, digital learning, and digital literacy experiences. Strategic planning often fails to provide clarity and efforts to truly identify and address digital divide gaps could greatly equip learners with digital skills. The main factors contributing to the digital inequities may not be identified as physical access only but rather a divide in digital skills/literacy to the extent in which populations are divided and excluded (Li & Li, 2021).

Invest in teachers and measure professional development efforts.

The pandemic has presented teachers with a renewed insight on the importance of participation in digital learning development, as now they are aware of their own digital skills, abilities, and limitations (Toto & Limon, 2021). This presents an opportunity for organizations to foster stronger development approaches and to identify gaps in digital competencies, teacher capabilities, and abilities to use technology to communicate well, or digital fluencies. Schools can look to the ISTE standards, Common Framework for Teaching Digital Competence, or TPACK as a starting point. TCEA is a leader in this area and is an essential partner in the solution for districts to begin addressing this issue. Investment in technology training cannot be an afterthought during the strategic plan process and is a required component to equip students with future-ready skills. Measuring the quality of teacher training and resources can provide insights into how financial allocation of professional development is impacting student engagement, use, and academic performance.

Live interaction for accelerated instruction will continue to matter.

Gaps in learning will require strategic planning to heavily invest in accelerated instruction platforms and approaches. Overcoming traditional barriers will be required of administrators to support positive learning experiences as an evidence-making approach within the multi-tiered system. Quality engagement with personalized feedback using technology can have a large impact toward addressing gaps. For example, Houston Community College is offering students virtual support through online advising and tutoring services via a virtual lobby. These types of initiative can go a long way to improving our response using technology as leaders.

Chandra, S., Chang, A., Day, L., Fazlullah, A., Liu, J., McBride, L., … & Weiss, D. (2020). Closing the K–12 digital divide in the age of distance learning. Common Sense and Boston Consulting Group: Boston, MA, USA.

Gorski, P. (2005). Education equity and the digital divide. AACE Review (Formerly AACE Journal), 13(1), 3-45.

Korman, H., O’Keefe, B., & Repeka, M., (2020, October 21). Missing in the Margins: Estimating the Scale of the Covid-19 Attendance Crisis. Bellwether Education Partners. Retrieved from: https://bellwethereducation.org/publication/missingmargins-estimating-scale-covid-19-attendance-crisis#Why%20aren’t%20students%20attending%20school.

Vishkaie, R. (2020). The pandemic, war, and sanctions: Building resilience for the digital divide in education. Interactions, 27(4), 36-37.

Li, S., & Li, E. (2021, July). The Impact of Digital Divide on Education in USA Amid COVID-19 Pandemic. In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (pp. 571-576). Springer, Cham.

Toto, G. A., & Limone, P. (2021). From Resistance to Digital Technologies in the Context of the Reaction to Distance Learning in the School Context during COVID-19. Education Sciences, 11(4), 163.

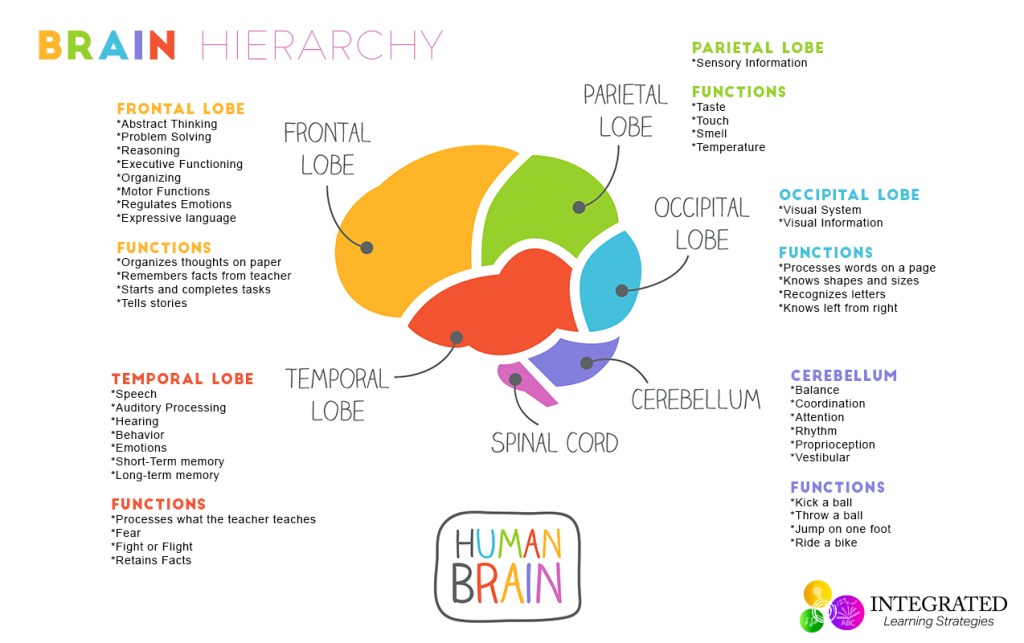

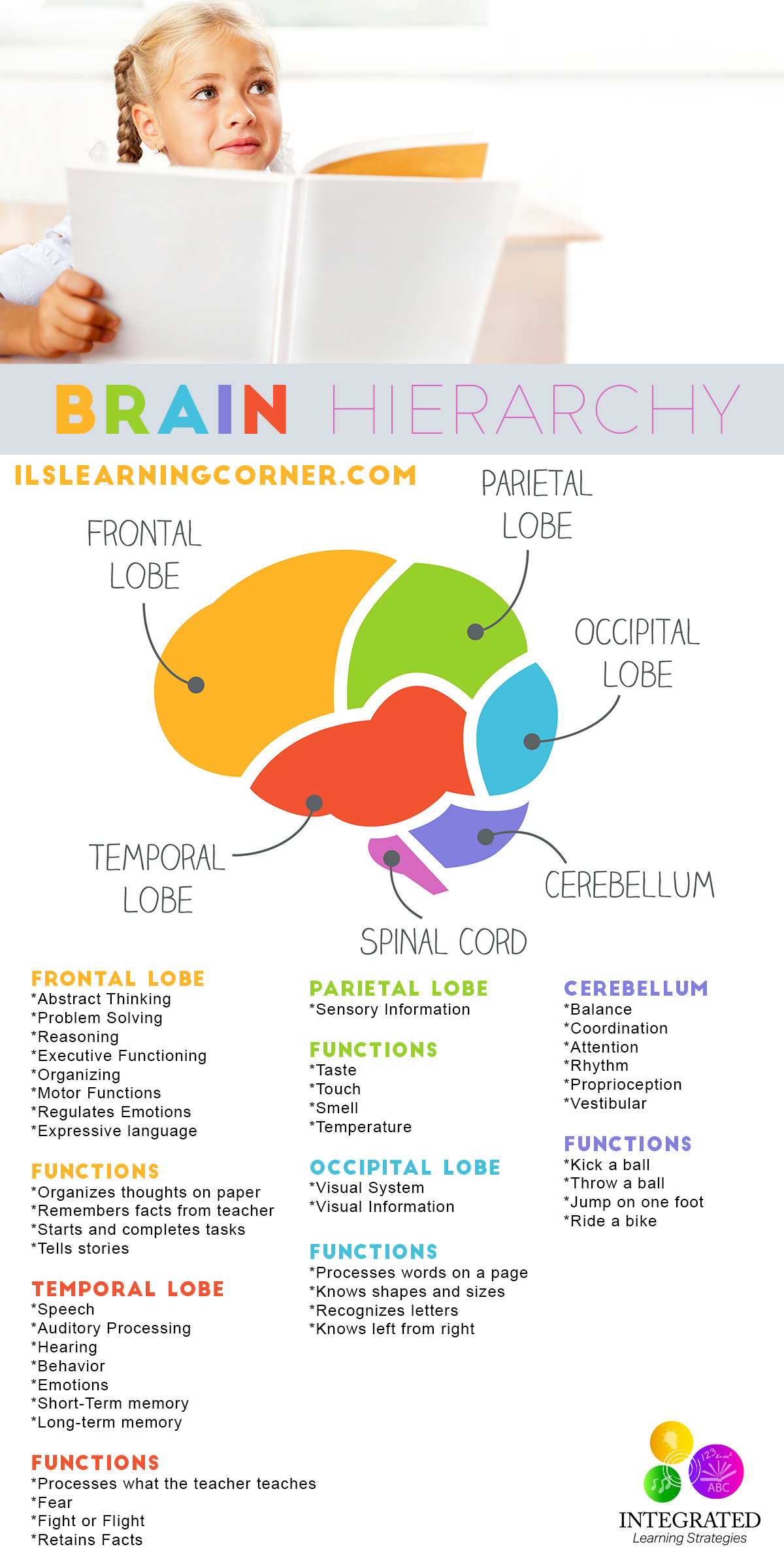

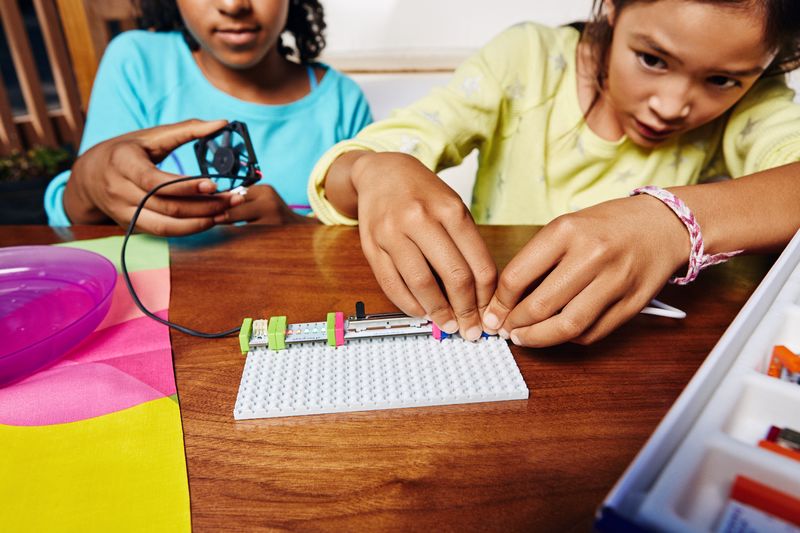

Social constructionism “relies on the centrality of language to mediate what people come to understand about their lived experiences” (Avermann, 2011, p. 205). Constructionist environments support “active learning” approaches in which learners are engaged in building their own public objects or artifacts. Active learning emphasizes cognitive processes occurring during the actual construction of the object. The public nature of the final object or artifact is also understood to be important (Beynon & Roe, 2004). The “maker movement emphasizes learning through direct experiences, hands-on projects, inventions, and is based on a constructionist learning theory even if members and advocates of the movement are unaware of the theory” (Stager, 2013). Papert (2000) advocates that Piaget’s belief of all learning takes place in discovery is accurate. However, Papert extends this idea to suggest that setting learners “to the task of re-empowering the ideas of being learned is also a step toward re-empowering the idea of learning by discovery” (p. 723). Papert (1999) underscores the importance of Piaget’s theory of constructivism and the nature of knowledge. Challengers of Piaget’s constructivism often refer to experiments demonstrating knowledge acquired by infants. However, Papert stresses “Piaget as a giant in the field of cognitive theory, the difference between what a baby brings and what the adult has is so immense that the new discoveries do not significantly reduce the gap but only increase the mystery” (Papert, 1999, p. 105). Papert’s Knowledge Machine” introduced the world to a new theory of learning, constructionism, which “synthesized revised insights into human development, systems theory (cybernetics) and how we think about learning (epistemology)” (Maser, 2013). Technology based modeling and methods of teaching with technologies deliver alternative methods to teaching, providing learners with choices that engage the learner in an improved learning experience (Burbaite, Stuikys, & Damasevicius, 2013). While at MIT, Papert developed Logo, designed to introduce children to programing and robotics as early as 4th grade. Children received instant feedback from a real and physical response to their creation using technology. Papert envisioned robotics as being extremely influential to children at a young age. Learners perform higher when engaged in an activity that is meaningful to them, and robotics along with programing languages encourages curiosity and experimentation beyond the actual syntax (Pierce, 2013). Papert led many research projects to study the effects of constructionist theories with at risk populations and in high-risk environments. These projects attempted to build an alternative approach to the learning environment. Despite obstacles, students proved to be successful. Experiences from Papert’s work towards building a community of learning centered on constructionism continues to guide the future design of learning environments (Stager, 2013).

Social constructionism “relies on the centrality of language to mediate what people come to understand about their lived experiences” (Avermann, 2011, p. 205). Constructionist environments support “active learning” approaches in which learners are engaged in building their own public objects or artifacts. Active learning emphasizes cognitive processes occurring during the actual construction of the object. The public nature of the final object or artifact is also understood to be important (Beynon & Roe, 2004). The “maker movement emphasizes learning through direct experiences, hands-on projects, inventions, and is based on a constructionist learning theory even if members and advocates of the movement are unaware of the theory” (Stager, 2013). Papert (2000) advocates that Piaget’s belief of all learning takes place in discovery is accurate. However, Papert extends this idea to suggest that setting learners “to the task of re-empowering the ideas of being learned is also a step toward re-empowering the idea of learning by discovery” (p. 723). Papert (1999) underscores the importance of Piaget’s theory of constructivism and the nature of knowledge. Challengers of Piaget’s constructivism often refer to experiments demonstrating knowledge acquired by infants. However, Papert stresses “Piaget as a giant in the field of cognitive theory, the difference between what a baby brings and what the adult has is so immense that the new discoveries do not significantly reduce the gap but only increase the mystery” (Papert, 1999, p. 105). Papert’s Knowledge Machine” introduced the world to a new theory of learning, constructionism, which “synthesized revised insights into human development, systems theory (cybernetics) and how we think about learning (epistemology)” (Maser, 2013). Technology based modeling and methods of teaching with technologies deliver alternative methods to teaching, providing learners with choices that engage the learner in an improved learning experience (Burbaite, Stuikys, & Damasevicius, 2013). While at MIT, Papert developed Logo, designed to introduce children to programing and robotics as early as 4th grade. Children received instant feedback from a real and physical response to their creation using technology. Papert envisioned robotics as being extremely influential to children at a young age. Learners perform higher when engaged in an activity that is meaningful to them, and robotics along with programing languages encourages curiosity and experimentation beyond the actual syntax (Pierce, 2013). Papert led many research projects to study the effects of constructionist theories with at risk populations and in high-risk environments. These projects attempted to build an alternative approach to the learning environment. Despite obstacles, students proved to be successful. Experiences from Papert’s work towards building a community of learning centered on constructionism continues to guide the future design of learning environments (Stager, 2013).